Reconstructing history

De Loutherbourg’s stage innovations were many, and had immense impact . He invented raked set pieces that provided a vanishing point and staggered cut pieces that framed the stage. Instead of footlights, which cast actors’ faces in horrific chiaroscuro, he used illumination above the proscenium, behind coloured glass slips. Changes and mixes simulated sunshine, moonlight, or volcanic rays, turning plants green to crimson. If lighted from the front or rear, slanted light from numerous sources exposed different scenes on translucent backcloths. Performers appeared in entrances or windows, leapt from bridges, and scaled castle walls for the first time because the set was appropriately carpentered in three dimensions.

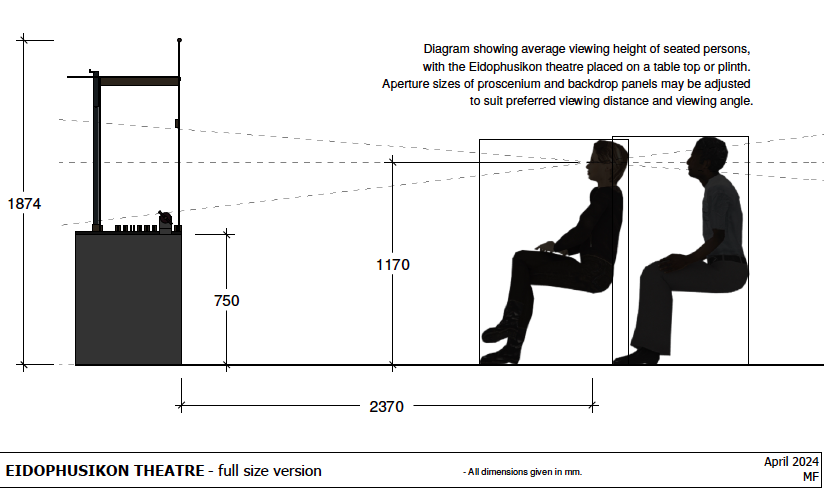

The original Eidophusikon built in 1781 was entirely analogue and used smaller versions of the stage light and set innovations he had pioneered at Drury Lane. Loutherbourg saw no distinction between the mechanical and the magical. It was an imaginative entertainment in a box ten feet wide, six feet high, and eight feet deep, located at one end of a darkened salon, and featuring a sequence of moving sceneries accompanied by a harpsichord. The Eidophusikon, rightly recognised as one of cinema’s earliest antecedents, employed tiny models and mechanised sets to construct accurate depictions of various scenarios, each with its own narrative arc full of sound and action.

Robert Poulter has been making amazing miniature theatres based on or replicating the Eidophusikon for many years, and regularly exhibits them (along with his bigger practice of paper theatre performance) in performances and festivals. Robert gave me an immense amount of help in thinking about how to devise my own interpretation of the Eidophusikon. While Robert’s Eidophusikons are more of a replication of de Loutherbourg’s, mine aims to merge this archaic art form with contemporary art.

Lighting

De Loutherbourg’s stage lighting was – obviously – not electric. For the majority of de Loutherbourg’s stage career, candles served as the source of illumination. They were frequently mounted on big chandeliers hanging over the audience, as well as in wall sconces. Chandeliers would be hung above the stage, and candles could be set on the floor (footlights) and along the stage’s sides using ladders. They leaked wax, smoked, and required frequent re-lighting and trimming. De Loutherbourg employed mirrors, glass panels, and reflectors to improve brightness and focus illumination.

In 1780, Swiss scientist Aime Argand invented the modern oil lamp, which quickly replaced the candle as the major light source. This type of oil lamp was invented by. Its output ranges from 6 to 10 candelas, which is brighter than prior lamps. Because the candle wick and oil burned more completely than in other lamps, the wick needed to be trimmed less frequently. It is uncertain whether de Loutherboug used the Argand light in the Eidophusikon.

Obviously it was not permitted for me to use candles in the Eidophusikon at Swedenborg House. The Eidophusikon – then and now – is made of wood and is highly flammable. De Loutherbourg’s original Eidophusikon – which he sold in late 1782 – ended up catching fire and perishing. I wanted to keep the analogue feel of the Eidophusikon, but I needed to use modern available lighting systems. I consulted with the artist diz_qo (Mark Watson), a veteran of many years lighting stages and providing video shows for live events. Mark advised me on the use of LED lighting strips which are light and versatile. Additionally, I purchased several lamps which provide colored moving lights.

Sound

The Eidophusikon can not provide its own sound. De Loutherbourg worked with well-known musician Michael Arne to provide music for the show; Arne played the harpsichord. Arne was the son of Thomas Arne, who is the most significant composer of 18th-century stage music. Michael was also an alchemist, like de Loutherbourg. He wrote nine operas, worked on at least 15 others, created some incidental music for plays, and published seven song collections. He composed a small amount of music for harpsichord and organ, with some published in 1761. Arne, following in his father’s footsteps, composed in the popular galant style, blending English folk music with Italian opera.

I invited my long-time friend and frequent collaborator on art events, Takatsuna Mukai, to compose original music for the Eidophusikon. Taka composed and recorded each scene using a variety of instruments and techniques and then played live violin over them. The music is beautiful and fully brings to life the mystical experience of the sublime..