Loutherbourg’s Eidophusikon Reimagined

Swedenborg House, The Bloomsbury Festival London Oct 18-27. Exhibition open daily, performances tba

‘Eidophusikon’ comes from eidoion (‘phantom’, ‘image’, or ‘apparition’) + phusis (‘nature’ or ‘natural appearance’) + eikon (‘image’ or ‘likeness’)

Mechanical landscapes, an engineered sublime

‘Into the Sublime: the Eidophusikon Reimagined’ is Artist in Residence Gillian McIver’s reconstruction and reimagining of the iconic Eidophusikon, a milestone in theatre history. It was created by the 18th-century French painter Philip James de Loutherbourg RA, who served as a stage designer for David Garrick at Drury Lane, creating sublime stage effects that astounded audiences. It was a small-scale example of the cleverly-engineered stage sets Loutherbuourg created for the stage.

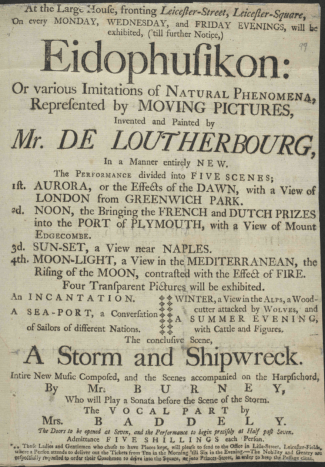

A Popular Entertainment

The original Eidophusikon was a small-scale stage set that combined dramatic paintings, lights, gauze, coloured glass, and smoke to create scenic effects. The original was 304.8cm wide; the reinterpretation will be only slightly smaller. Loutherbourg’s effects included panoramas of London, storms at sea, and scenes from Milton’s Paradise Lost. The Eidophusikon opened in February 1781 in Lisle Street, Leicester Square – which was Loutherbourg’s home and in its second season transferred to a rented premises. The Eidophusikon was a popular entertainment in London and is widely regarded as a crucial forerunner to cinema.

Swedenborg’s ideas about art and science, material work and the afterlife, and his vision of the Divine

Gillian’s Eidophusikon will follow Loutherbourg’s plan of a five-scene performance while incorporating current contemporary art (by herself and a number of London and international artists) to explore Swedenborg’s ideas about art and science, material work and the afterlife, and his vision of the Divine. Loutherbourg knew Swedenborg and most likely painted the ascribed portrait, which is on display at Swedenborg House.

Loutgerbourg’s fascination with sublime landscapes is the key to his work as a stage designer. The painter was not interested in portraits*. Very few of his portraits remain, and even the Swedenborg one does not appear to have been finished. Since portrait painting was one of the main ways artists got lucrative commissions, Loutherbourg had to find another way of making a living.

By working in the theatre, Loutherbourg continued to paint his landscapes for the existing market, but also was able to experiment and explore ways to create landscapes that achieved a realistic sublime on a truly grand scale.

With the Eidophusikon, a ‘show’ without a story or actors, he was able to achieve pure landscape, happening in time. The sun rises and sets, the waves dash against the sinking ship, the volcano erupts, and other natural phenomena appear on the small stage, untroubled by characters or human drama.

‘the eagerness of curiosity is so great, that as the scenes follow each other in a quick succession, the spectators too frequently rise from their seats, as to destroy the perspective effects of the picture’ The Morning Herald 1781

“the Eidophusikon was a rather complex theatrical machine, a multimedia apparatus reminiscent of Baroque contraptions but adapted to a new Romantic taste for the sublime by combining in a moving diorama naturalistic images accompanied by dramatic lighting and ambient sound effects. The Eidophusikon is a kind of transitional medium because it consists of a mechanical apparatus designed to produce an artificial imitation of suggestive natural effects. The key to these effects is motion: in short, the Eidophusikon translates into spectacle a vision of nature in motion.” Massimo Riva

Eidophusikon performance

*Loutherbourg’s disinclination to make portraits was shared by his close friend Thomas Gainsborough. Gainsborough, with a family to support, did give in to the necessity of portraiture, though he far preferred landscapes, complaining in his private correspondence that he was sick of painting rich people and wished he could just stay in the village and paint the countryside. However, he is one of Britain’s greatest portrait painters, so his loss is our gain.