Emanuel Swedenborg was not an occultist, but quite a few of his followers were. Philip James de Loutherbourg in particular, along with his artist friends Richard Cosway and John Flaxman, among others. What is the connection between Swedenborg and the occult in the late 18th century?

At the core of Swedenborg’s beliefs was the concept of absolute human freedom upheld by divine love. He taught about the existence of multiple heavens and hells, as well as the idea of conjugal relations among departed souls. Furthermore, he professed a belief in the presence of extraterrestrial beings from other worlds. Drawing freely from Neo-Platonism, he described a material world infused with benevolent spirits. His writings, gradually published over the years, offer a collection of visionary insights. His followers, deeply invested in their own personal spiritual pathways, selectively embraced messages from Swedenborg that resonated with their personal objectives. It was only with the establishment of the New Jerusalem Church – an institution not created by Swedenborg and founded after his death– that this spiritual liberty began to be formalized into a doctrine. However, the tendency of his followers to interpret his teachings independently never fully went away. As a result, many – especially non-members of the church and early adopters of Swedenborg’s ideas - could hold fundamentally different views to Swedeborg 9and each other) on various concepts.

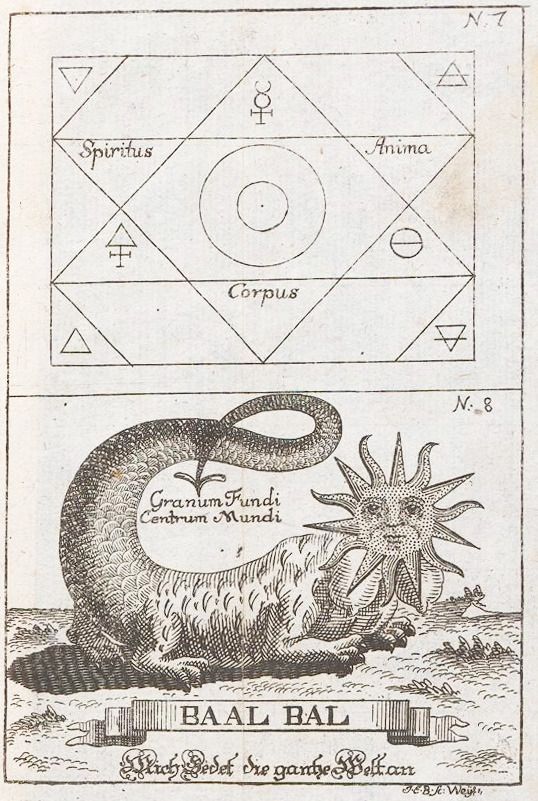

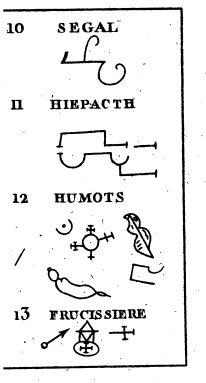

A good example of this is the issue of magic. According to Paul Kléber Monod in Solomon’s Secret Arts: The Occult in the Age of Enlightenment (2013) Swedenborg wasn’t engaged with the occult at all. He associated it with Satan or false religion. He felt that occult practices were what he called ‘profane abuses of the divine order’. However, many of his followers were drawn to magic, both natural and supernatural. Many tended to combine elements like Böhmeism with Swedenborg’s teachings in their minds. They did not see an essential contradiction between Swedenborg, experimental and theoretical science, astrology, alchemy, or necromancy.

Many if not most of the magical practitioners in London at the time were, as well as followers of Swedenborg, also Freemasons. Loutherbourg, Cosway, Flaxman and Cagliostro were just a few of the most prominent. Although there is no evidence that Swedenborg was himself a Freemason, his ideas had a profound impact on the development of European masonry. Benedict Chastanier, a French-speaking, Swedenborgian resident in London, advocated the creation of a specifically Swedenborgian type of masonry, which would include the study of the occult. Few London Swedenborgians would have been ignorant of recent pro-occult developments in Continental Freemasonry.

Swedenborg was not the only scientist to believe in metaphysics and spirituality. Joseph Priestley, a prominent scientist of the time, was also a Unitarian minister. He asserted the existence of an ‘unseen substance’ and the presence of a benevolent God responsible for the inexhaustible variety in nature. Priestley’s view was that while the universe is comprised of perceivable matter, the soul is of a divine nature beyond human perception. Additionally, he proposed that with a benevolent creator governing the laws of nature, the world and its inhabitants would ultimately reach a state of perfection. According to his perspective, evil exists as a result of an imperfect understanding of the world. These concepts are also deeply connected to alchemy. This line of thought blurs the distinct boundaries between Priestley, science, and alchemy.

One of the most important things is that the occult revival of the 18th century encompassed so many different points of view that we can’t really consider it a single movement. Even relatively well-defined groups like the Swedenborgians had many differences of opinion, and deep divisions existed on the most fundamental issues, such as eternal punishment. Occult thinking in this period was often personal and individualistic.

The essential difference I think, between mysticism and occultism is that mysticism is philosophical and contemplative and occultism is active and practice-based. What people think or believe might not even differ so much. One issue that seems to have perplexed people from all varieties of occult and spiritual viewpoints was the existence and role of spirits in the natural world. Swedenborg, for example, believed that spirits were differentiated by the degree of love that they manifest in their worldly lives, and the afterlife simply eternalises the earthly condition of the human spirit, so death was a continuation of the essential state of a spirit. The spirits came to him because he was in a state of receptiveness. Occult practitioners like Loutherbourg and Cagliostro, on the other hand, sought to bring supernatural power or understanding of the supernatural to bear on nature, by ritually raising spirits, invoking them for specific purposes.

In this sense, occult thinking was always a counterpart to natural philosophy or science even in the Enlightenment.