Philip James de Loutherbourg’s stage effects were the sensation of the late 18th century. Arriving to London’s Theatre Royal Drury Lane in 1771, he and actor-manager David Garrick made theatre history by bringing a new, exciting realism to the stage. From realistic acting directed by Garrick to phenomenal set and special effects design by Loutherbourg, the English theatre was forever changed.

But Loutherbourg’s spectacular and convincing creations were the result of his alchemical practice as well as his knowledge of theatre design. He created lighting effects in his alchemical laboratory using his own chemical compounds and other methods before transferring them to the stage. When he arrived at Drury Lane, he quickly showed a tremendous ability to create genuine renderings of nature, including water effects such as weather, storms, and the appearance of beautiful landscapes. This was accomplished by carefully combining painted movable scenery and lighting effects with multiple transparencies of translucent silk materials dyed using his own closely guarded recipes and procedures. Loutherbourg never revealed the secrets of his stagecraft, and when he died, he directed that all of his papers be destroyed by his wife Lucy. He did not want to share his secrets. It’s unclear why this was the case.

Working with David Garrick, who was an innovator himself, Loutherbourg brought real spectacle to the stage. According to Andrew McConnell Stott:

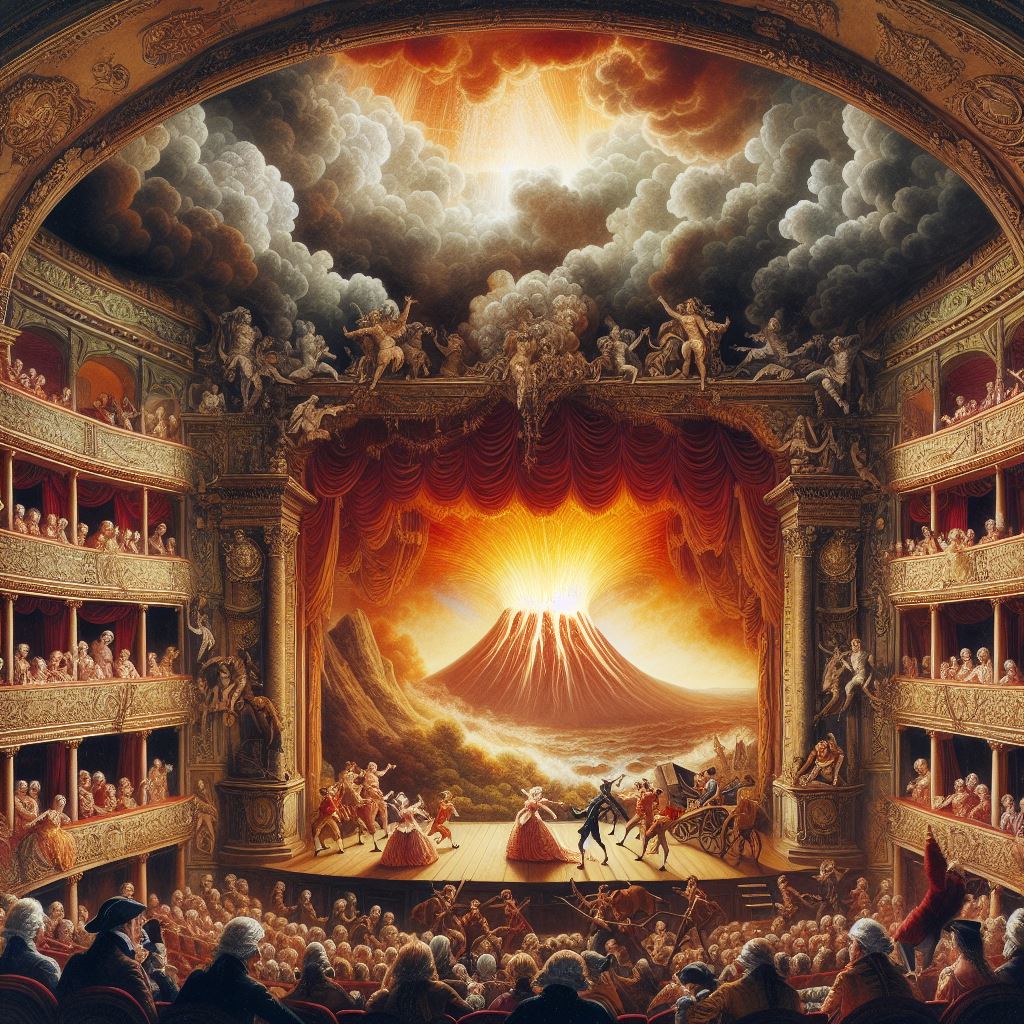

‘His revolution brought depth and consistency to any scene: raked set pieces created a vanishing point, and cut pieces framed the stage at staggered intervals. He removed the footlights, which had a tendency to cast the actor’s faces in ghoulish chiaroscuro, and instead installed lighting above the proscenium behind slips of colored glass. These could be shifted or combined to produce the effect of sunshine, moonlight, or volcanic glows, even changing the color of foliage from green to red. He cast angled light from multiple sources that revealed different scenes onto transparent back cloths depending on whether they were lit from the front or back. Scenery was properly carpentered in three dimensions, allowing actors to interact with it for the first time, appearing in doorways or at windows, leaping from bridges and scaling castle walls. He designed all the costumes to give the production a sense of its own coherence, and most importantly, he set it all behind the proscenium arch, to give the audience the sense they were watching a moving picture.’

There are some descriptions of his stagecraft and what he brought to the plays that Garrick and Sheridan produced at Drury Lane

For A Christmas Tale (1773), which dealt with magic and magicians, Loutherbourg devised spirits and demons behind a rock that split apart to reveal a castle set in a fiery lake. The following year, he created an ancient Egyptian set for the drama Safona, featuring a Temple of Osiris and subterranean catacombs. For sure this was excellent stagecraft, but Loutherbourg believed in it as a mirror of true magick. To him, his art, including his stage work, was an outcome of his magickal practices. The two were tightly integrated.

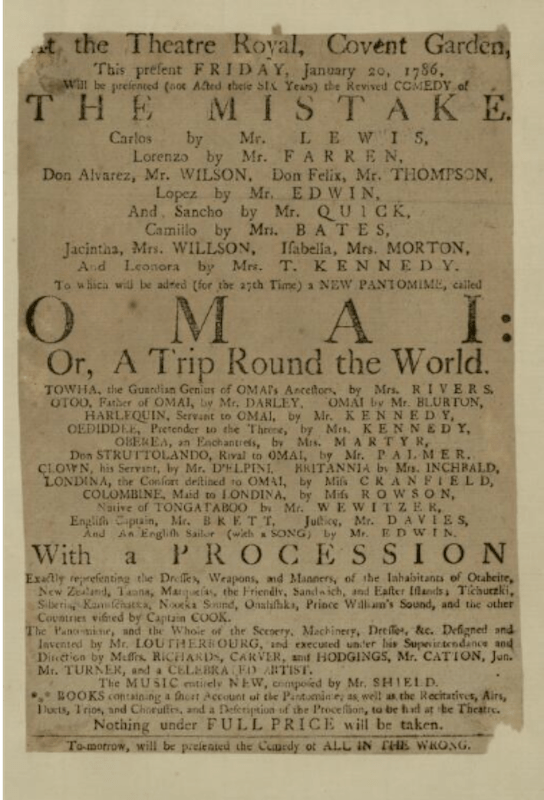

For the 1785 theatrical masterpiece, Omai: A Trip Around the World, Loutherbourg crafted a celestial apotheosis of Captain Cook. The play narrated the true story of Omai, a Polynesian prince brought to England by Captain Cook. Loutherbourg’s stage effects included South Sea Islander sorcerers, ghosts, and a ‘guardian spirit’ who appeared in a blaze of liquid fire at the play’s climax. In a patriotic tableau, Captain Cook ascends to heaven, accompanied by Britannia. This scene may have been influenced by symbolic rebirth conceptions derived from Loutherbourg’s involvement in Freemasonry. Notably, the martyred captain’s ascension featured him carrying a sextant – which resembled a masonic compass. (Kleber Monod)

‘Verisimilitude was his occult science, a way of showing that what we see is the thinnest of veils.’

-Andrew McConnell Stott ‘Stage Light’

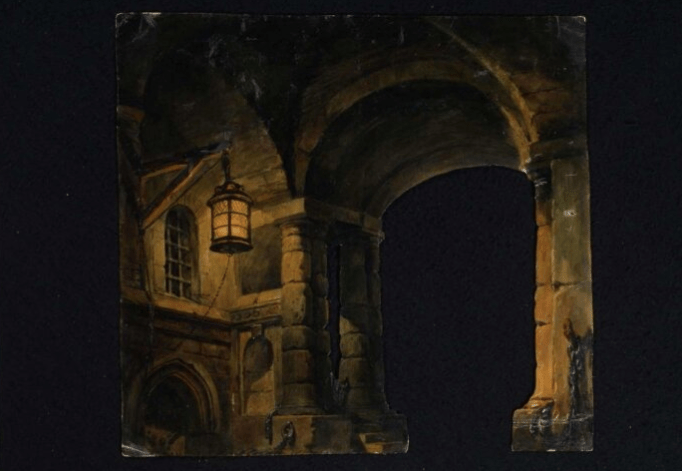

No less than in his paintings, Loutherbourg’s set models at the V&A demonstrate his remarkable ability to create realistic scenes on a grand scale. His work contributed to the development of the “realistic sublime” that influenced Romanticism and continues to influence forms of art such as cinema and video game design today.

However, according to Stott, Loutherbourg’s approach to realism went beyond mere replication of reality. He sought to convey the idea that what we perceive as “real” can be summoned, that illusions can evoke real sensations, and that the boundary between the material world and that of the spirit is not only permeable, but that perceptions can be crafted, manipulated, and brought to life. The distinction between reality and illusion becomes blurred in his work, raising the question: what is truly real, and what is mere illusion? Perhaps, in the world of art, both coexist, and it is here that the true essence of the spiritual realm is found.

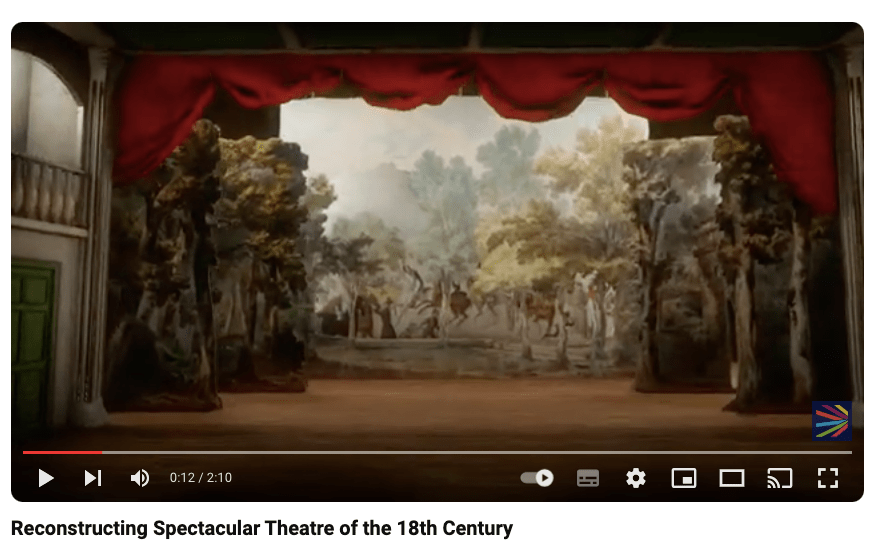

View a Reconstruction of Loutherbourg’s stage designs

The digital reconstruction is a collaboration between David Taylor (University of Oxford) and Arcade Ltd (https://arcade.ltd); it uses photographs of three maquettes in the Victoria & Albert Museum. The project was by sponsored by TORCH: The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities.

Bibliography

Andrew McConnell Stott. Stage Light:The life of artist and scenographer Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg, and the role of the occult in the history of special effects.

Paul Kléber Monod. Solomon’s Secret Arts: The Occult in the Age of Enlightenment (2013)