considering the art and magic of illusions

What is a ‘magic lantern’?

A magic lantern is an early form of image projector, essentially the granddaddy of slide projectors and movie machines. Invented in the 1600s, it was a box with a light source (initially a candle, later upgraded to oil lamps and even limelight) and a lens system that projected images painted on glass slides onto a wall or screen. Imagine a dimly lit room, people gathered around expectantly, and then a ghostly image of a dancing skeleton or a fantastical creature materializing on the wall – that’s the kind of wonder the magic lantern brought. It was used for entertainment, education, and even religious purposes, showcasing everything from spooky ghost stories to scientific diagrams.

Before the magic lantern, there were devices like the Camera Obscura.

The camera obscura, which translates to “dark room” in Latin, is an optical device that has been used for centuries to project an image of the outside world onto a surface inside a darkened room. It is considered to be the precursor to modern photography and played a significant role in the development of the art form.

The basic principle of the camera obscura involves a small hole or aperture in one side of a darkened chamber. Light from the outside passes through this aperture and projects an inverted image onto a screen or wall opposite the hole. The image is formed due to the rectilinear propagation of light, where rays of light travel in straight lines until they are interrupted by an object.

The camera obscura was first described by the ancient Chinese philosopher Mozi in the 5th century BCE. However, it was the Arab scholar Alhazen who provided a detailed explanation of its workings in the 11th century. Alhazen’s work on optics greatly influenced later scientists and artists, including Leonardo da Vinci.

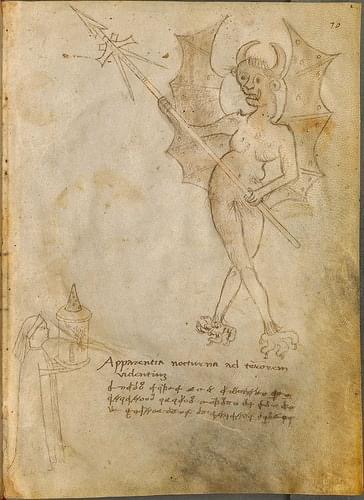

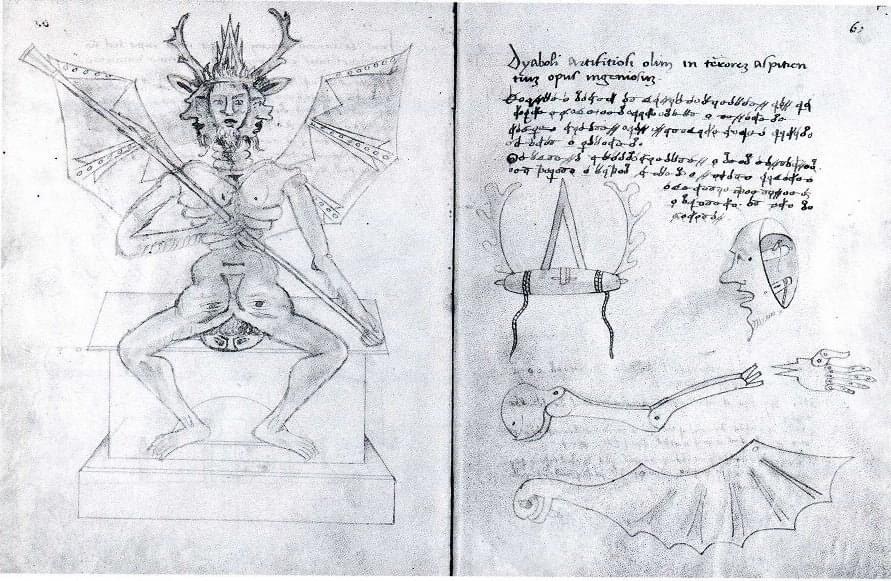

Camera Obscura is described in Giambattista della Porta’s Natural Magick. The 1589 edition of Natural Magick emphasizes the value of the camera obscura to painters. As a way of exploiting that phenomenon, della Porta also advises the use of the camera obscura to astonish and entertain. I presume people were already using the camera obscura to entertain. Apparently (I haven’t been able to verify this) a Renaissance scholar, de Villeneuve, orchestrated elaborate entertainment with sound effects using a camera Obscura. But magic lantern projections could also be used to frighten the credulous.

the magic lantern show

Early magic lanterns used candles, but oil lamps and eventually limelight offered brighter and more controlled illumination. The magic lanterns used glass plates, or slides. These were hand-painted with transparent areas that allowed light to pass through, creating the projected image. The slides could be simple or incredibly detailed, depicting scenes, characters, or educational diagrams. A series of lenses focused the light from the source onto the slide and then projected the enlarged image onto the screen.

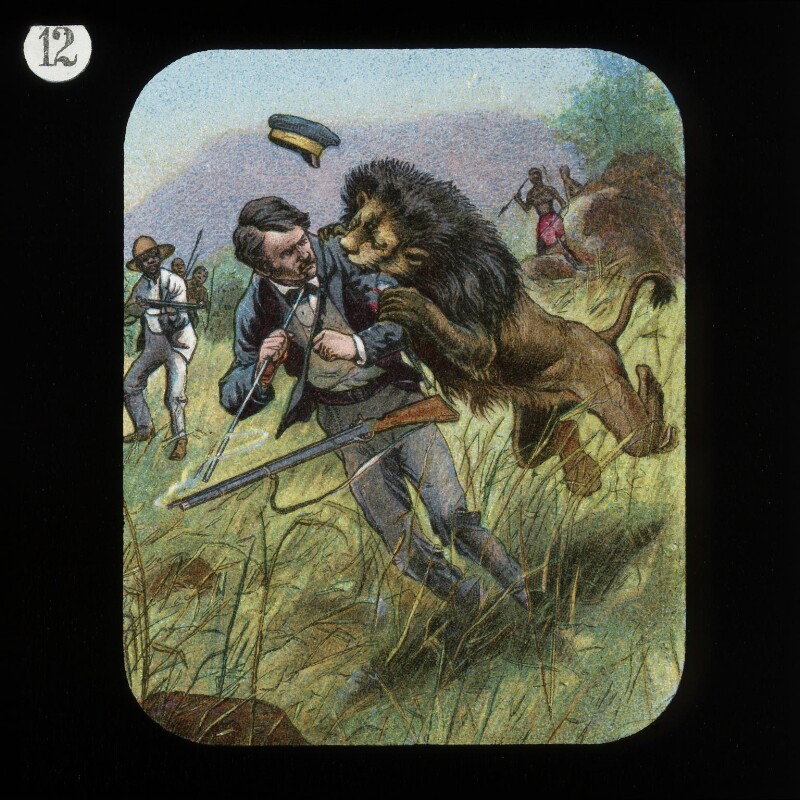

An example of a glass painted magic lantern slide:

by Unknown artist, published by The London Missionary Society

glass magic lantern slide, circa 1900

NPG D18385

Don’t think the Magic Lantern is a dead art form. The Magic Lantern Society has a substantial membership of lanternists and enthusiasts who put on lantern shows all over the world! If you are fortunate enough to see one you will be amazed at how beautiful they are.

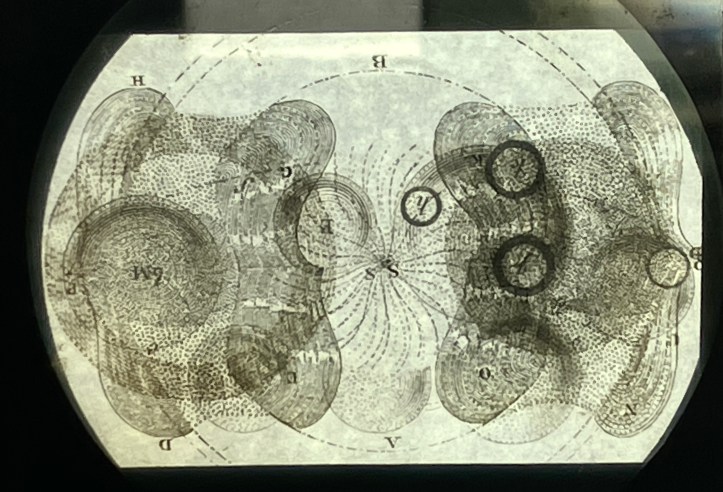

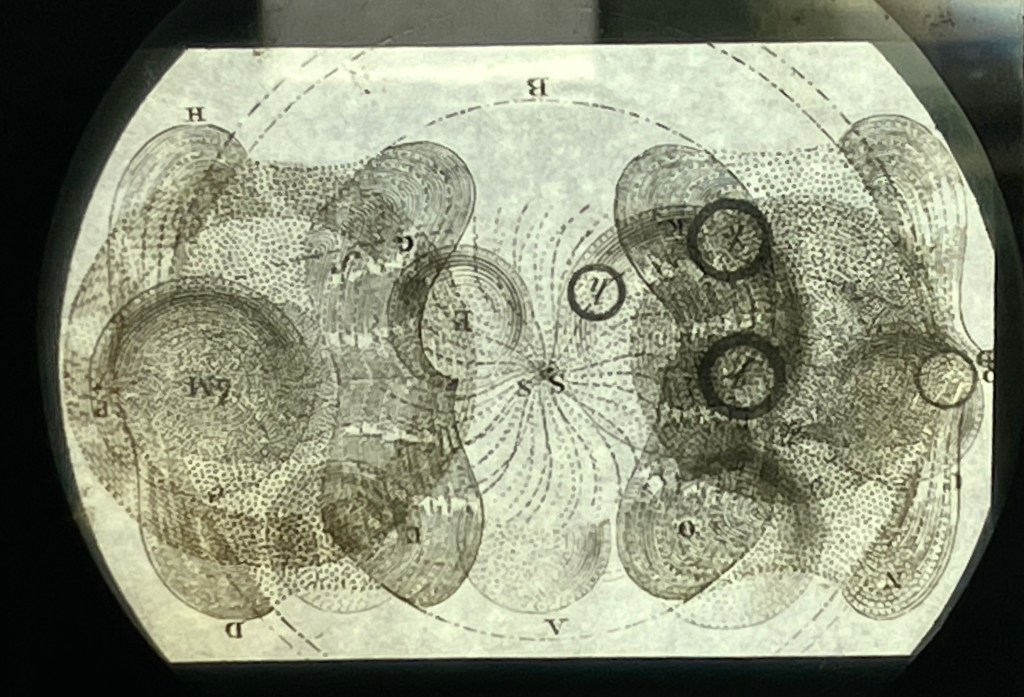

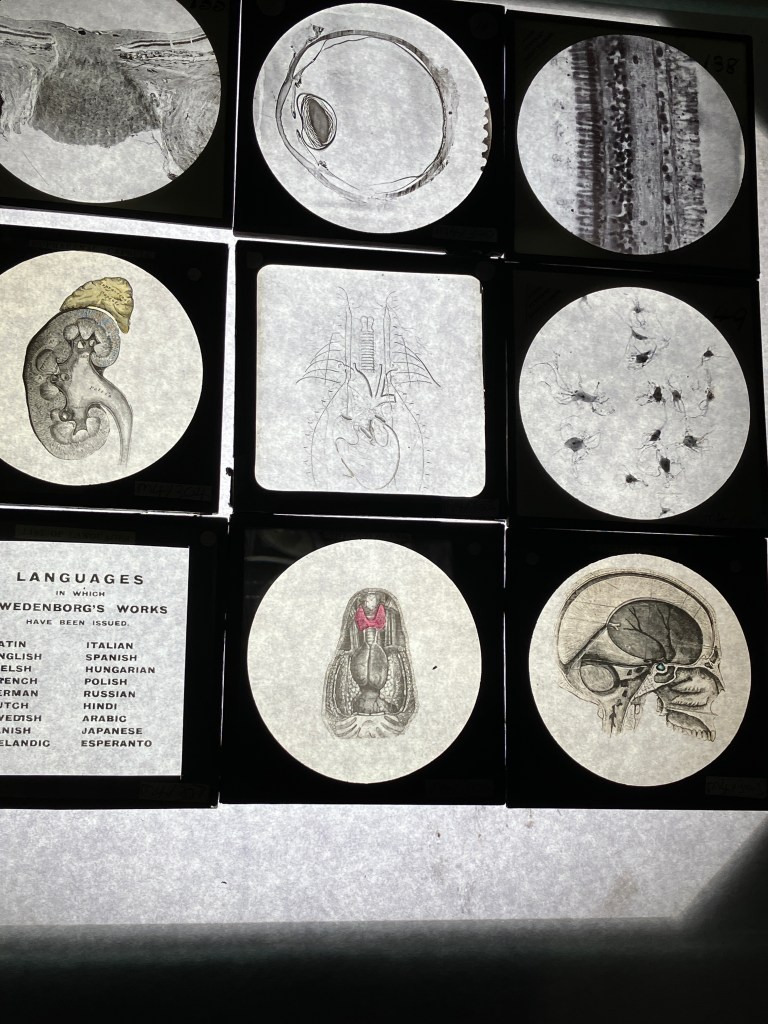

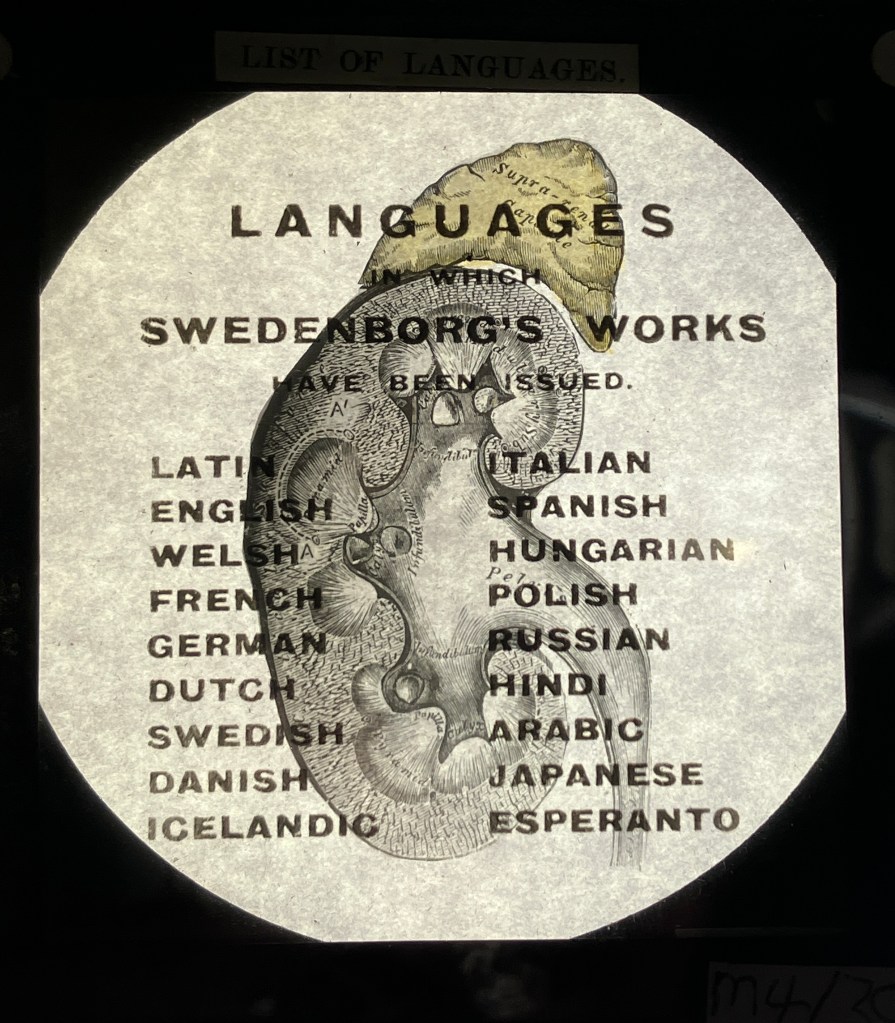

Swedenborg House in Bloomsbury has a large collection of magic lantern slides from the early 20thC. They contain documentary material of Swedenborg’s re-interrment on the 140th anniversary of his death, in 1912/1913, when his remains were transferred from London to Uppsala Cathedral in Sweden. There are also many portraits of Swedenborg taken form paintings and busts. In addition, I found two boxes of diagrams and drawings taken from his books.

Together with my friend, we experimented with layering the slides and creating strange and interesting combinations, as the glass layers added different scintillations and textures, creating a range of illusions.

what’s magick about the magic lantern?

On the surface of it, nothing. It’s simply technology. However as we’ve seen with (possibly) Villeneuve and certainly Della Porta, projections can have magical qualities. Tricking the eye to see the immaterial was among the skills of the celebrated magicians of yore. I would argue that the manifesting of illusions in this way has unimportant role in reminding us that ‘real’ is so subjective. The projected image seems ‘real’ and in a sense it is, it’s a real image, but then what is the image? It is not the thing projected, is it? The image is not the slide. Yet the image has no material existence. It exists because of the convergent relationship between the eye and the light, with the glass plate intervening. We’re so used to seeing images on screens now that we forget that seeing images that have no materiality is very very recent in human history. Even two hundred years ago, such images were astounding and unusual and still redolent of magic.

Today, images abound and we pay little attention to them, though we are pretty much enslaved to them. Therefore it is worth looking back to the early days of image creation to see how and why the conundrum of real vs image came about and why it was important. To me, the art of illusion and image making IS magick because it reminds us that the material is not all there is – and that so much of what we think we know depends on our senses, yet they are limited.

Johannes Kepler and Vopiscus Fortunatus Plempius, in separate scientific investigations, sought to distinguish between ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’ images. The phenomeon of the projected image inspired them to do this. Kepler, Plempius and others specifically distinguished between the pictura which has a fixed reference point, and the imago, which is purely imaginative.

Pictura is Latin for painting (to paint, pingere) and until the development of projection there was no other way to ‘make’ an image appear. Kepler points out that a pictura is something which is made, has a fixed reference point; imago is the ‘imagined picture’ that exists only in the imagination (the ‘mind’s eye’). Kepler noted, using the camera obscura, how optics create the illusion of an imago out of a pictura (e.g. a projection of a drawing using a magic lantern, a projection of a real-life object or a scene using a camera obscura). When Plempius experimented with the ox-eye, demonstrating how the eye renders a representation of the world, he sought to find a word to describe how “you, standing in the darkened room, behind the eye, shall see a painting that perfectly represents all objects from the outside world,” he writes. Thus the word used to identify a projected image was the same word used to identify a painted image: both were “paintings” even through early modern scientists understood the material differences between a two-dimensional painting and a projection. But this is the first indication that there is a shared language of visual representation that overlaps, elides and synchronises across art forms.